This past weekend, approximately 20 Guilders made a six hour pilgrimage north on I-94 to the Twin Cities to visit our friends at Arms & Armor and the Oakeshott Institute. Despite having known Craig Johnson and Chris Poor for many years, ironically, only a handful of us had ever been up to visit them in their natural, sword-filled, habitat. Craig agreed to put together a shop tour, lecture series and handling of the beautiful pieces that once belonged to the renowned sword researcher and historian, Ewart Oakeshott.

This past weekend, approximately 20 Guilders made a six hour pilgrimage north on I-94 to the Twin Cities to visit our friends at Arms & Armor and the Oakeshott Institute. Despite having known Craig Johnson and Chris Poor for many years, ironically, only a handful of us had ever been up to visit them in their natural, sword-filled, habitat. Craig agreed to put together a shop tour, lecture series and handling of the beautiful pieces that once belonged to the renowned sword researcher and historian, Ewart Oakeshott.

Our visit began with a tour of the Arm & Armor workshop, aka, “where the magic happens”. A&A makes some of the finest replica swords and training weapons in the business; and so our descent into the basement where their shop lies felt a bit like a trip down into Vulcan’s forge. I confess that I hadn’t pictured the facility being so *big*. It’s a sword lover’s dream, filled with all manner of weapons and armour, both finished and various stages of being “in process”. It was also fascinating to look at the pieces that Chris and Craig have kept for themselves, from one of a kind polearms to jousting harness, and see a time line of Arms and Armor’s history in the 30 years since Chris Poor first started his business, while still being a jouster on the Renaissance fair circuit. Craig showed us their forge, grinding wheels, casting molds, and explained to us how A&A designs and produces their weapons. Then he let us wander about and play, which we gleefully did.

Our visit began with a tour of the Arm & Armor workshop, aka, “where the magic happens”. A&A makes some of the finest replica swords and training weapons in the business; and so our descent into the basement where their shop lies felt a bit like a trip down into Vulcan’s forge. I confess that I hadn’t pictured the facility being so *big*. It’s a sword lover’s dream, filled with all manner of weapons and armour, both finished and various stages of being “in process”. It was also fascinating to look at the pieces that Chris and Craig have kept for themselves, from one of a kind polearms to jousting harness, and see a time line of Arms and Armor’s history in the 30 years since Chris Poor first started his business, while still being a jouster on the Renaissance fair circuit. Craig showed us their forge, grinding wheels, casting molds, and explained to us how A&A designs and produces their weapons. Then he let us wander about and play, which we gleefully did.

From there, we headed over to the Oakeshott Institute. Ewart Oakeshott spent his life trying to rectify misunderstandings about the medieval sword, and to draw an appreciation for them both as artwork and as perfectly designed tools. Therefore, when he died in 2002, his will bequeathed his beautiful collection with the idea of creating a hands-on, educational museum. To house the museum, Chris Poor has purchased an old, 19th c church for the Institute, which the A&A boys are slowly renovating. Based on the amazing woodwork, vaulted ceilings and the renovations we saw going on, the Institute will be a small, but lovely museum once it is finished.

Keith Alderson met us at the institute, and was our first presenter. Keith is an ABD (“all but done”) PhD student at the University of Chicago, specializing in late medieval, German books. He also comes from a background in Korean martial arts, kendo and knife-fighting. This combined background has given him a unique, and valued insight into the German fencing texts and I was eager to hear his discussion. Keith detailed how the four guards of the Liechtnauer system went through a conceptual evolution over the two centuries that the art flourished, beginning as leger, which Keith sees as a general position from which one engages in a certain type of fighting, and becoming hut, specific positions, or “guards” that one stands or moves into. This presentation is going to be published in a forthcoming compendium by Freelance Academy Press, and I will be interested to see how his ideas are received in the larger community.

Keith is also a a student of the modern Bowie knife system taught by Pete at Alliance Martial Arts and Jim Keating of Comtech. Keith made an interesting point that German Ms. 3227a, the oldest Liechtenauer text (aka the “Doebringer” Fechtbuch) proclaims that all longsword fencing derived from the use of the messer, or knife. The messer was a single-edged weapon with a clipped point and “false edge”, which came in varying lengths, from a long knife to a two-handed falchion. Keith then pointed out that the messer continued right into the modern era with the Bowie knife, and showed how the “back cuts”, or false edge blows , taught with that weapon relate directly to many of the specialized blows, or Meisterhau of German swordsmanship. This comparison was used as a lens to interpret the historical material because the mechanics of early American Bowie knife fighting are well understood, and the actions in use could be compared not just the mechanical, but the tactical qualities of the different sword blows. The larger message was that there is a readily identifiable set of tactical and mechanical advantages that one gains when using a double-edged weapon uses both edges to strike along all eight of the basic angles of attack .

Keith is also a a student of the modern Bowie knife system taught by Pete at Alliance Martial Arts and Jim Keating of Comtech. Keith made an interesting point that German Ms. 3227a, the oldest Liechtenauer text (aka the “Doebringer” Fechtbuch) proclaims that all longsword fencing derived from the use of the messer, or knife. The messer was a single-edged weapon with a clipped point and “false edge”, which came in varying lengths, from a long knife to a two-handed falchion. Keith then pointed out that the messer continued right into the modern era with the Bowie knife, and showed how the “back cuts”, or false edge blows , taught with that weapon relate directly to many of the specialized blows, or Meisterhau of German swordsmanship. This comparison was used as a lens to interpret the historical material because the mechanics of early American Bowie knife fighting are well understood, and the actions in use could be compared not just the mechanical, but the tactical qualities of the different sword blows. The larger message was that there is a readily identifiable set of tactical and mechanical advantages that one gains when using a double-edged weapon uses both edges to strike along all eight of the basic angles of attack .

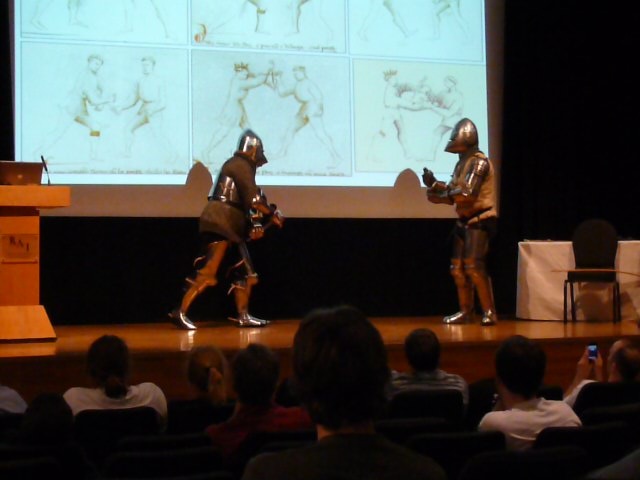

Keith was then joined by Craig in a demonstration on how the Oakeshott team is applying some of these ideas in their own martial arts practice. They walked us through a fair amount of translated passages from the “Dobringer” manuscript, and pointed out that the admonishment to cut, thrust and slice can be used as an order of operations for making an attack and pursuing follow-up actions. Craig also showed us a specialized training sword he has designed to teach students to cut in a narrow arc, instead of “round housing” their blows, and a number of Guilders tried their hands at the “sword on a rope”.

The next presenter was Josh Davis, a member of the Institute and part of the Arms and Armor shop team. then showed us the first complete harness he had made (German, late 15th c), and talked about his project in making it, and how cool it was to submit it as part of his academic work towards a bachelor’s degree in Medieval Studies. It was a nicely made harness by any standard, but was particularly impressive for the first harness made by someone who has been armouring for only three years! He had the opportunity to fly over to England and examine a number of Gothic harnesses up close and personal to gather the understanding necessary for this undertaking, which is something that cannot be overstated as important knowledge for armour manufacture. You know, kinda like handling original swords to see what a sword should feel like …

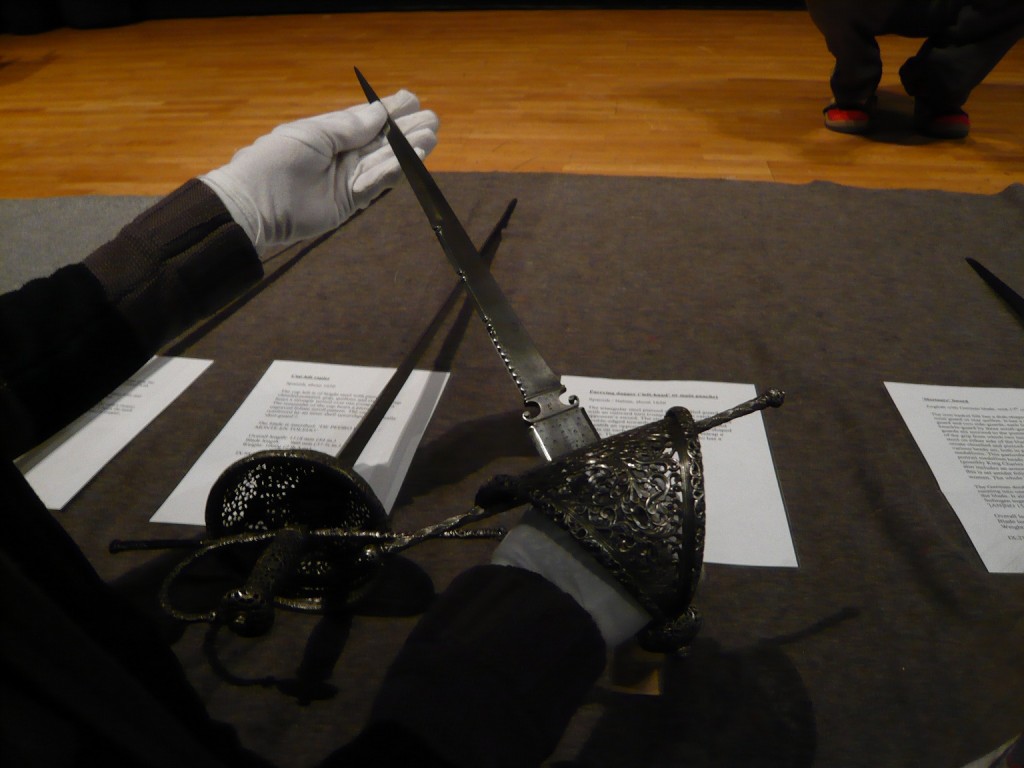

After Josh’s lecture we came to the part where we got to play with the pretties. Pictures can do them better justice than words, in the absence of having them at hand. There were several medieval one handers from the 11th – 15th centuries, including Ewart’s prized sword “Moonbrand”, a pair of 5th century, Frankish saxes, several 16th – 17th century rapiers, several mortuary and basket-hilted swords, and an 18th c hanger in pristine condition that just begged to be used.

Following dinner, the Oakeshott folks treated us to a handling of some of Bronze Age pieces in their collection. Three swords, at least one spear point, a few axe heads, and a very very old mace head from Sumer that was dated to about 2000 BC. It was just astounding to handle pieces of such antiquity that were still in such usable condition – one of the bronze swords still has areas that gleam golden through its green patina.

The group reconvened on Sunday morning for Craig Johnson’s lecture about the history of European metallurgical science, text sources and illustrations relating to the same (mining the ore to smelting the blooms to pounding and forming the billets with hammers or water powered trip hammers). Of particular interest were images of more than one female blacksmith or armoursmith shown in a guild workshop context. We also went through an overview of hardness testing and ratings, examples of hardnesses on several surviving medieval and Renaissance swords (each of which were not consistent in their hardness, even within the length of one edge). There was also reference on modern steel hardness and properties, and what modern customers expect and demand a sword be made from, without any real justification for that demand based on historical examples. Which is to say, modern people look at modern tools and demand that swords be made to some of the specs of modern tools (~50-52 Rockwell hardness), without understanding that such is far harder and homogeneous than the original pieces, and thus likely unnecessary to the finished product’s function. There was also a fascinating look at the blacksmith’s tools, and how well formed they were already by 600 AD, and how they are EXACTLY the same as what we see until the Industrial Revolution. As Craig reminded us a number of times, these craftsmen had thousands of years to figure out exactly how to do what they wanted, and what was the best way to make it. They figured it out, and more often than not, when Craig and company have tried to engineer a way around a historical process involved in the manufacture of a piece, they discovered very late that it was far, far easier to do it the way it was originally done, and the result was perfectly fine.

The group reconvened on Sunday morning for Craig Johnson’s lecture about the history of European metallurgical science, text sources and illustrations relating to the same (mining the ore to smelting the blooms to pounding and forming the billets with hammers or water powered trip hammers). Of particular interest were images of more than one female blacksmith or armoursmith shown in a guild workshop context. We also went through an overview of hardness testing and ratings, examples of hardnesses on several surviving medieval and Renaissance swords (each of which were not consistent in their hardness, even within the length of one edge). There was also reference on modern steel hardness and properties, and what modern customers expect and demand a sword be made from, without any real justification for that demand based on historical examples. Which is to say, modern people look at modern tools and demand that swords be made to some of the specs of modern tools (~50-52 Rockwell hardness), without understanding that such is far harder and homogeneous than the original pieces, and thus likely unnecessary to the finished product’s function. There was also a fascinating look at the blacksmith’s tools, and how well formed they were already by 600 AD, and how they are EXACTLY the same as what we see until the Industrial Revolution. As Craig reminded us a number of times, these craftsmen had thousands of years to figure out exactly how to do what they wanted, and what was the best way to make it. They figured it out, and more often than not, when Craig and company have tried to engineer a way around a historical process involved in the manufacture of a piece, they discovered very late that it was far, far easier to do it the way it was originally done, and the result was perfectly fine.

After the lecture we adjourned together for lunch, and then it was time for the long drive home. Many thanks to Craig, Chris, Keith and the whole Oakeshott team for their hospitality and sharing of knowledge. We hope to repeat this next year!

(You can find more photos of our trip in the CSG Flickr Gallery.)