(c) Robert Rutherfoord, June 2018

A tempo is a movement that the opponent makes within the measures […] The reason why the name tempo was given to the movements made while fencing is that the time employed to make one movement cannot be employed to make any other. -Salvator Fabris, 1606

I was enticed to end this blog with the previous quote, 1) because writing is hard 2) because Fabris addresses both parts of the title of this blog in very clear terms. But… as the philosopher that each Italian swordsman references, directly or not, says: “We must take this as our starting-point and try to discover- since we wish to know what time is- what exactly it has to do with movement.” -Aristotle, c. 4th century BCE.

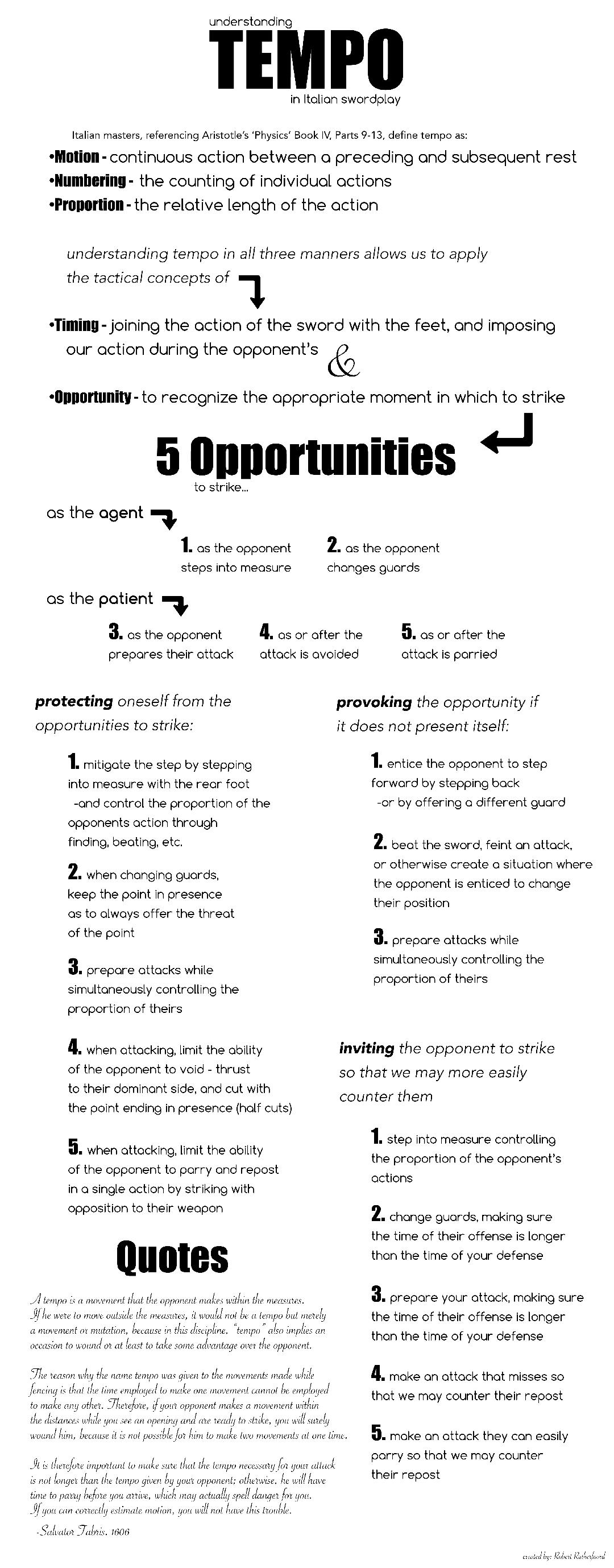

Aristotle, tying together the concepts of Time and Motion in parts 7 through 13 of ‘Physics’ (Book IV), identifies three core components of their relationship. First, time directly follows motion and the two are inexorably linked, thus we can say any continuous motion that is encapsulated between two moments of rest is a single unit of time, or a single tempo. Second, because any motion can be divided into parts, and those parts follow one after another, we can identify those motions (as they relate to each other) as being: before, now, and after. Thus, motion can be counted or numbered by their parts. Lastly, because time is continuous, but objects can move and come to rest at different intervals, their locomotion can be identified as either proportionally long or short. We can thus say that tempo is defined by both by its motion and its rest.

For a simple illustration of all three concepts at work, lets look at someone standing still, who then begins walking forward, and then stops. In the first definition, “Time is Motion” as soon as the figure starts walking to the time he stops, he created one continuous action and is thus a single tempo (“what is moved is moved from something to something, and all magnitude is continuous.”-Aristotle). In the second definition, “Numbering the Motions” each step can be counted individually, so each step is its own tempo (“Hence time is not movement, but only movement in so far as it admits of enumeration.”-Aristotle). And in the third definition, “Motion is Proportional” each step can be made longer or shorter by the distance each covers. Wider steps are proportionally longer than shorter steps, but each still being a single tempo (“It is clear, too, that time is not described as fast or slow, but as many or few and as long or short. For as continuous it is long or short and as a number many or few.”-Aristotle).

When Aristotle writes, he refers to the things that are moving as ‘bodies.’ In fencing, each ‘body’ is a part of the fencer and his weapon that is capable of closing distance, mainly the hand (tied to the weapon or defensive implement), the body (which can come forward or back) and the feet (which carry and support the body). Each one of these parts can make a ‘tempo’ in each of the three above definitions. Not only can they make a tempo on their own, often they create tempi together.

The joining of these bodies in motion creating tempi, I will call ‘Timing.’ This timing not only refers to how the fencer joins their own motions but how he imposes his motions between (or inside of) his opponent’s. When Fabris says: “the time employed to make one movement cannot be employed to make any other” and “make sure that the tempo necessary for your attack is not longer than the tempo given by your opponent” he is referring to the timing of our action as well as its proportional length (respectively). For example, if the opponent moves his sword from right to left, he can cannot in the same instance, move his sword from left to right. While this ‘body’ is in motion, a proportionally shorter motion should be made by the opponent to ensure the attack can not be parried. The imposition of timing our action within the opponent’s is referred to as ‘in tempo.’ (“Further ‘to be in time’ means for movement, that both it and its essence are measured by time (for simultaneously it measures both the movement and its essence, and this is what being in time means for it, that its essence should be measured”-Aristotle).

With the consideration of Timing, and the essence of the nature of fencing (to hit while not being hit), certain opportunities arise, mainly when is it appropriate to strike the opponent. Giovanni dall’Agocchie, c. 1572, gives us 5 opportunities or tempi, which one can appropriately time a proportionally shorter attack than our opponent’s attempt at a defense (or at the very least making a defense very difficult).

In reverse order that Dall’Agocchie lists them, they are: 1) “while he raises his foot, that’s a tempo for attacking him” 2) “as he injudiciously moves from one guard to go into another, before he’s fixed in that one, then it’s a tempo to harm him” 3) “when he raises his sword to harm you: while he raises his hand, that’s the tempo to attack” 4) “when his blow has passed outside your body, that’s a tempo to follow it with the most convenient response” 5) “once you’ve parried your enemy’s blow, then it’s a tempo to attack.” The reason I have listed them in reverse order is because when read this way, they are presented in a certain order of precedence, from the time the opponent begins to close measure to the point he is attacking you (ie. “the movement[s] that the opponent makes within the measures”). Each moment in time can be ‘numbered’ this way.

The first two opportunities apply to the Agent (the fencer who is seeking to strike first). If the opponent is stepping forward, he can not simultaneously step back, and if he is changing guards, he can not occupy the space he just left.

The last three opportunities apply to the Patient (the fencer dealing with the Agent’s attack). As the opponent raises their hand to attack they are momentarily less able to deal with an attack themselves. While Dall’Agocchie specifically mentions raising the hand as a method to prepare an attack, this idea can be expanded to deal with all methods of preparing an attack, in short, anything the Agent does to put their sword and body into a position to deliver their intended strike (be it feint, beat, pulling the arm back, raising it, etc.). Now, if the Patient is actually receiving the strike, he can deal with it in two main ways, 1) void 2) parry. There are many forms of these two actions and also a continuum of actions between the two that incorporate both a void and a parry. While the opponent is extended for their attack (thus leaving a strong defensible position), the Patient can apply option 1 or 2 and return a strike (a repost), or more preferably, timing their action so that they strike simultaneously against the attack.

With the above knowledge of the appropriate times to strike, it can be seen that both the Patient and Agent have opportunities to wound, so the matter of protecting oneself from them is paramount. In short, to ensure safety while one moves, and thus creating a tempo or opportunity to be struck, their motions should be proportionally smaller than the opponents necessary action to strike. For instance, if one wishes to step into measure, the step should be small, or it can be made on the rear foot, or it can be timed with an accompanying motion of the sword to create a barrier in which the opponent’s sword has to move around (thus lengthen the proportionate time of his strike). If one wishes to change guards, they can make small changes, or keep the point in presence to dissuade an attack. If the fencer wishes to prepare an attack, it should be done mindful of the position of the opponent’s weapon, making sure the preparation and subsequent attack is shorter than the motion of the opponent’s weapon to its intended target.

The question then becomes, if I know what opportunities exist to strike, how to protect myself from those moments, if the opponent does not offer one, how do I create one in which to attack? The concept of Provoking deals with this question. Dall’Agocchie defines these types of actions like this:

“Said provocations, so that you understand better, are performed for two reasons. One is in order to make the enemy depart from his guard and incite him to strike, so that one can attack him more safely (as I’ve said). The other is because from the said provocations arise attacks which one can then perform with greater advantage, because if you proceed to attack determinedly and without judgment when your enemy is fixed in guard, you’ll proceed with significant disadvantage, since he’ll be able to perform many counters.”

These actions are made with the intent to force or entice the opponent to move, thus creating a tempo in which to attack. As Dall’Agocchie mentions, Provocations come in two forms, the first, a proactive motion that forces the opponent to create a tempo, and second, a passive invitation to entice him to strike. However, both of these methods require a motion by the provocateur. So, even if we seek to provoke a tempo, it is required of us to give a tempo. Again, the tempo we create to force one from our opponent needs to be proportionately smaller than the opponents motion to strike, or otherwise create a situation where this is true.

Bibliography

“Physics by Aristotle” http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/physics.4.iv.html. Translated by R. P. Hardie and R. K. Gaye

Leoni, Tom. Art of Dueling. Chivalry Bookshelf, 2006

Swanger, Jherek. On The Art of Fencing. Online, 2007